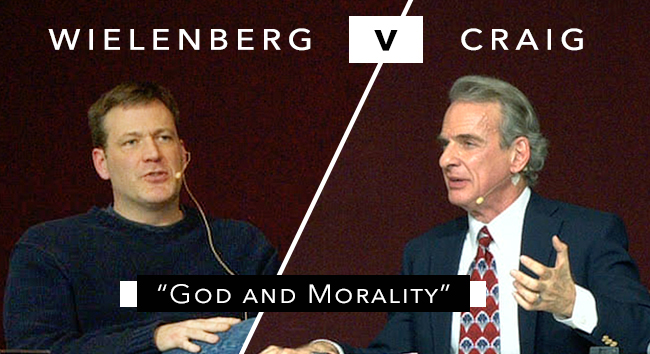

Moral Debate With Erik Wielenberg, Part One

April 22, 2018 Time: 17:46

Summary

A debate for which Dr. Craig rigorously prepared on the Moral Argument.

KEVIN HARRIS: Just when you thought you had heard the best debate on the moral argument, Dr. Craig does another one. Welcome to Reasonable Faith with Dr. William Lane Craig. I'm Kevin Harris. The next two podcasts are a two-part series on this debate. Dr. Craig talks about some of the behind-the-scenes prep that went into this debate, the importance of this debate with Dr. Erik Wielenberg, and more. So stay tuned. The next two podcasts are a two-part series on this great debate. By the way, go to ReasonableFaith.org and be sure that you are up on all the resources that are available there, and you can make your gift easily and quickly right there at ReasonableFaith.org to bless this ministry. We thank you so much. Here is part one covering a debate with philosopher Dr. Erik Wielenberg.

Dr. Craig, Erik Wielenberg is a philosophy professor at DePaul University. The two of you had a debate. This was a different sort of debate. Talk about where it took place and also how you put the debate together in advance.

DR. CRAIG: The debate was at North Carolina State University. It was organized by Adam Johnson who is with Ratio Christi, which is a campus Christian organization. Adam had studied Wielenberg’s critique of theistic ethics, or ethics based in God, and wanted to give a theist a chance to reply to Wielenberg’s very strong criticisms of theistic ethics in his published work. So he contacted me about having a debate with Erik Wielenberg, and contacted Wielenberg as well. We were willing to participate in this debate but under the condition that it wouldn’t be an extemporaneous or spontaneous debate which would give the rhetorical advantage to the more skilled speaker and debater. Rather, what we would do is exchange our speeches in advance so that the opponent would have a chance to read through our speech, write a response to it, reflect on it, talk to others about it, refine it, revise it, and then finally send it to the opponent. So over a period of about fourteen months we exchanged our speeches. I sent him my opening speech, and he had six weeks to write a response. He then sent that to me, and I had six weeks to write a rebuttal. I sent that to him, and he had six weeks then to write his rebuttal. And so it went right down through the final closing statements. The only extemporaneous part of the debate was the Q&A that followed the presentation of the speeches. We had agreed that once a speech was sent to the opponent no further changes could be made. So we would deliver the speech that we had written and had sent to our opponent. That way you couldn’t have any sort of revisions after the fact. You had to stick with what you had said. I thought that made for a very substantive debate because now you weren’t winging it and you weren’t responding off-the-cuff. You had time to reflect on your opponent’s arguments and positions. You had time to craft your response to make sure it fit within the word limit. These speeches each had word limits, and each of us would go right up to that limit virtually to the very word. So I know that he as well as I put a good deal of effort into formulating and wording it so that one would say as much as one could but not exceed the word limit. As a result you have got here a really, really substantive debate that we hope now to turn into a book on what is the best account of moral values.

KEVIN HARRIS: So not only the opening speeches but the rebuttals were written out as well?

DR. CRAIG: Yes. The entire debate apart from the Q&A.

KEVIN HARRIS: Including the closing statements?

DR. CRAIG: Yes, even the closing statements were done in advance.

KEVIN HARRIS: I have to ask you – I wonder if you have been almost of necessity put into the position of becoming an expert on the moral argument and ethics.[1] I tell you, you really find yourself having to talk about morals and ethics and ethics proper and applied ethics quite a lot, don’t you?

DR. CRAIG: That is true, and I find it rather ironic because our listeners may not realize that my main focus philosophically is not on arguments for the existence of God. It is on what is called the coherence of theism or the attributes of God, defending the coherence of the traditional concept of God. Over the years I have studied and written books on things like divine omniscience, divine eternity, divine aseity. Those have been my bread-and-butter issues as a philosopher. It has simply been on the side that I have also been involved in working on these theistic arguments. So I actually welcomed the opportunity to debate Wielenberg on this because this is his area of specialization. He is an ethicist. His critique of me in his published work was incisive and strong and needed to be answered. I couldn’t allow these criticisms to go unanswered, so I welcomed the opportunity to meet with him and to have this debate. It has helped me to hone my skills in areas like ethics, cosmology (I am thinking here of the fine-tuning argument), and metaphysics such as the ontological argument or the Leibnizian argument from contingency. In all of these different areas these theistic arguments have forced me to go deeper into the relevant fields of philosophy.

KEVIN HARRIS: “Godless normative realism” – is that how you would characterize his view? Is that his view?

DR. CRAIG: That is how he characterizes his view. That is his name for the view. Each element of that title is important. It is godless, that is to say it makes no appeal whatsoever to God. He is a naturalist and claims that his view is entirely consistent with scientific naturalism. It is realist in the sense that Wielenberg affirms the objectivity of moral values and duties. He thinks that there are certain things that are really good or really evil in a mind-independent way, and that we have actual moral obligations to fulfill and that we would be derelict if we did not do so. These are incumbent upon us to fulfill our moral duties. So it is a realism in that sense. But then it is normative realism. This means that the way our moral duties are determined is not through the commands of some higher lawgiver or authority but rather you weigh the moral value of the outcome of your choices and then you figure out which one, if either, has the greater moral value and that is the one that you are obligated to do. Your obligations arise from this comparative value of the outcomes. So for example, if you are thinking about stealing someone’s pocketbook, you would assess the moral worth of the state of affairs of stealing that pocketbook as opposed to not stealing it. You would see that not stealing it is better. It is morally better, and therefore you are obligated to do that and not the opposite. So that would be godless normative realism.

KEVIN HARRIS: This was a dense debate. An intense debate. Let’s see if we can get some of the highlights. Let’s first go to the case that you presented in your opening.

DR. CRAIG: As is typical in my debates, I defend two contentions – one is a positive one and one is a sort of negative one. The first contention is that theism provides a sound foundation for the objectivity of moral values and duties. Here I just very briefly laid out the view that moral values are grounded in God who is the paradigm of goodness and moral duties arise from his commands to us.[2] That was my first contention – a positive presentation of a theistic view. The second contention is that atheism doesn’t provide as sound a foundation for the objectivity of moral values and duties as does theism. The wording here is important. Wielenberg had severely criticized me for defending the view that if God does not exist, objective moral values do not exist. Through the work of theistic ethicists like David Baggett and Steve Evans and others I saw that someone who grounds moral values in God does not need to be committed to so radical a thesis as the one that I believe in and do accept – that if God does not exist, objective moral values and duties do not exist. Rather what Baggett and Evans and others claim is that given the objectivity of moral values and duties God is the best explanation of them. So you can have a non-theistic explanation, you can offer one for objective moral values and duties, but it is not as good as theism. So it is not as radical as my position. It is not committed to the position that on atheism there are no objective moral values and duties. You are just taking a more modest stance that theism gives a better explanation of the objectivity of values and duties.

KEVIN HARRIS: You are pushing a little harder, aren't you?

DR. CRAIG: Yes. In my work up to this point I have been, and I am still convinced of that thesis. But for the purposes of this debate I chose to defend the more modest thesis because that is easier to defend. So I defend the sort of Baggett-Evans view that atheism does not provide as sound a foundation for the objectivity of moral values and duties as theism. That difference is significant because in the debate Wielenberg tried to push me to defend my own personal view that atheism implies moral nihilism. As I pointed out, I am not defending that in tonight’s debate even if that is my personal opinion. He needs to deal with the contention as I have stated it and as it is defended by many theistic philosophers. So those were my two contentions.

KEVIN HARRIS: When he gave his opening speech what were his contentions?

DR. CRAIG: In Wielenberg’s opening speech and throughout the debate he offered three objections to basing the objectivity of moral values and duties in God. The first objection was: Craig’s view arbitrarily singles out divine commands as the only possible source of moral obligation. The second objection was: Craig’s view implies that non-believers have no moral obligations since many people are unaware of God’s commands and authority. The third objection was: Craig’s view makes morally wrong acts inexplicable since God inexplicably commands people to do what he knows they won’t do. God exacerbates the evil in the world by giving commands to people who he knows won’t obey them thus making their actions wrong, in effect. So those were his three objections.

KEVIN HARRIS: You came back with your rebuttal. How did you address those three?

DR. CRAIG: In the debate I tried to move through his objections as quickly as I could so that I could spend more of my time – the lion’s share of my time – in defense of my second objection that godless normative realism does not provide as sound a foundation for the objectivity of moral values and duties. What I said was, in response to the first objection that my view implies that the only possible source of moral obligation is divine commands, that that is false. On my view there can be a hierarchy of sources of moral obligation. For example, for children, their parents. Or for citizens of a country, the state. But God is the ultimate source of moral obligations in this hierarchy.[3] With respect to the second objection that my view implies that non-believers have no moral obligations, I appealed to an illustration given by Matthew Flanagan, a New Zealand philosopher, of someone walking along the beach and suddenly coming to a chainlink fence with a padlocked gate and a sign that says “No trespassing.” Flanagan says you can clearly recognize the authority and your obligation to go no further even though you don’t have any idea of the identity of the person who posted the prohibition. In exactly the same way, unbelievers may have the moral law of God and its demands written on their conscience or their hearts even if they don’t recognize the source of this as being from God. They can recognize their duties and their authority without knowing that it came from God. Then the third objection, you will remember, was why doesn’t God simply give commands to people who he knew would obey them if he were to give them. The odd thing about this objection is that it presupposes that God has middle knowledge. It presupposes God knows what people would do if they were given a divine command. And that is not an entailment of divine command morality. In fact, some of the most prominent proponents of divine command theory such as Robert Adams are determined opponents of middle knowledge and have written against it. So this was an objection that, though aimed at me personally because I believe in middle knowledge, isn’t really an objection to divine command theory or theistic ethics at all. I said much more about that as well but that would just be one weakness in that third of objection.

KEVIN HARRIS: I want to encourage people to listen to the debate and go through it. We are just highlighting.

OK, let’s stop right there, and we will continue right there where we left off next time on the behind-the-scenes look at this great debate with Dr. Erik Wielenberg on Reasonable Faith with Dr. William Lane Craig.[4]